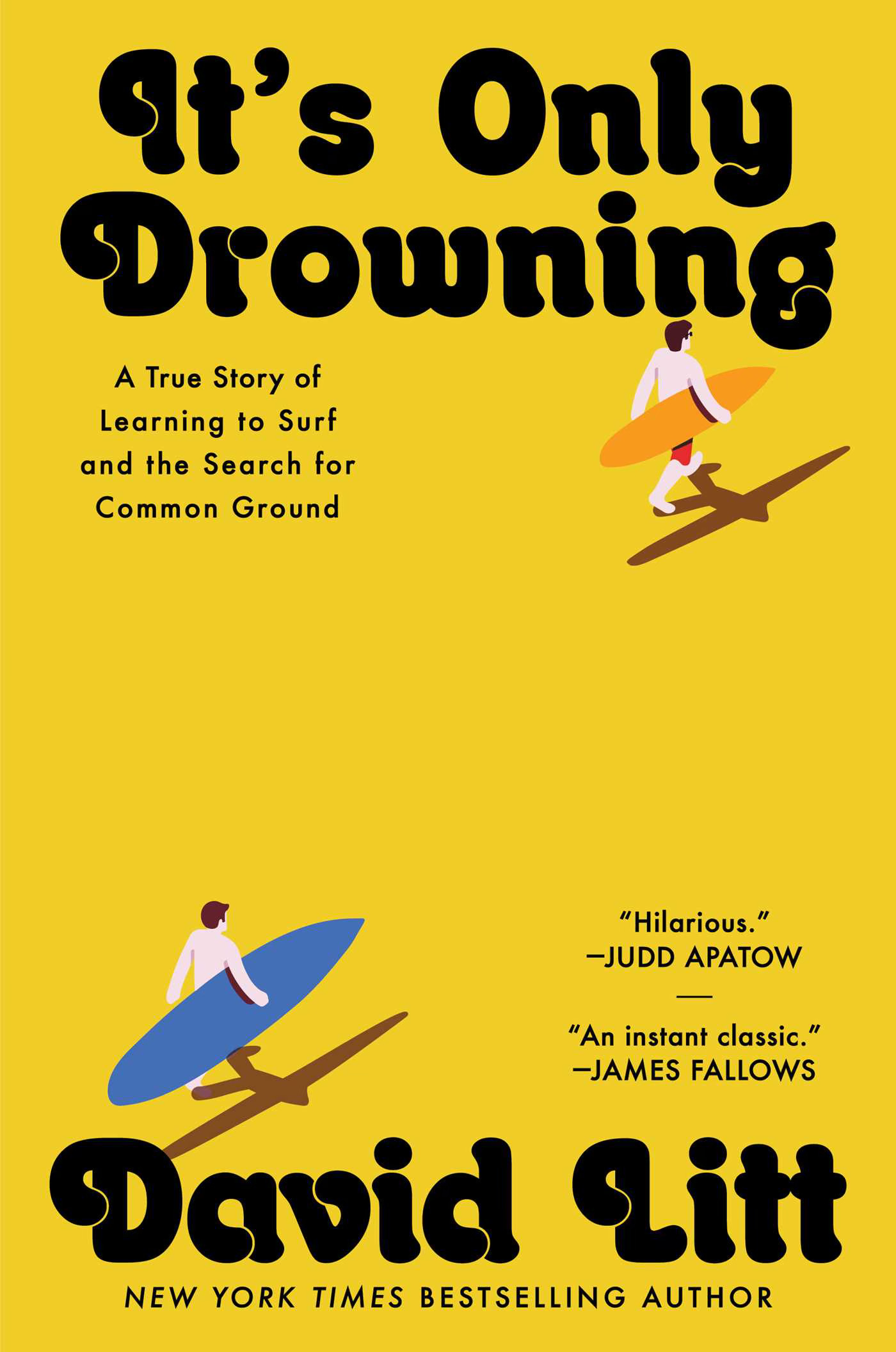

I’ve been working on It’s Only Drowning for three years. I’ve never been more proud of a piece of writing, or more eager for total strangers to read it. And yesterday, it hit shelves!

First off, thank you to everyone who already has ordered the book. Your comments, words of encouragement, and early reviews mean so much to me. I’ve said it before, and will say it again because it’s so true: first-week sales are crucial to a book’s chances of being widely read and having an impact.

Would I have chosen to launch my book the week we bombed Iran? Definitely not.

But thanks to you, the readers of this newsletter, It’s Only Drowning still has a fighting chance to break through.

If you haven’t picked up a copy yet, I hope you’ll get one today from Amazon, Barnes & Noble, or an independent bookstore via bookshop.org.

And also, in case you’d like to read some of the book first, here’s an excerpt. In fact, it’s the very first section of the very first chapter. I hope you enjoy it!

- David

CHAPTER ONE

Matthew Kappler is my brother-in-law, and we’re very different, and one of the biggest differences between us is that if I lived like him I would die.

Matt owns two motorcycles. The first is a Kawasaki for racing, the second a Harley for roaring down the Garden State Parkway at speeds he once described as “only” a hundred miles per hour. He’s an electrician, and a good one, in part because of how seriously he takes his work, and in part because of how casually he takes the prospect of violent shocks. Matt once threw out his back training to be a mixed martial arts fighter. I once threw out my back lifting a bag of cat litter.

We met in the summer of 2012. I’d been dating his older sister, Jacqui, for about a year, and she and I had driven up from Washington, DC, to visit her parents in New Jersey. At the time I was a twenty-five-year-old speechwriter for Barack Obama, with sensibly parted hair, an ergonomic keyboard, and a strong preference for the half-Windsor tie knot over the more conventional four-in-hand. Matt was living at home. He was twenty-two years old, on the tail end of a rebel-without-a-cause phase that had begun, as far as I could tell, at birth.

Because I was busy trying to impress Jacqui’s parents during that initial visit, I didn’t pay much attention to her brother. Matt first appears in my memory not as a person but as a muscle shirt–wearing specter, floating silently to the kitchen to blend a protein shake before disappearing into the garage to jam on his electric guitar. But more trips followed; my future in-laws lived minutes from the Jersey Shore, so Jacqui and I started coming up for beach weekends each summer.

Matt and I thus got to know each other a little better, and the better we got to know each other, the clearer it became that we had absolutely nothing in common. My professional life revolved around politics; he had never registered to vote. Matt played in a locally famous ska band; I played in a co-ed recreational Ultimate Frisbee league. My idea of a perfect meal was a bowl of homemade knife-cut noodles, studded with bits of pork and drenched in chili oil, from a hole-in-the-wall restaurant near the university where I studied on a summer fellowship that sent Ivy League undergraduates to Beijing. His was chicken tenders.

I didn’t dislike Matt. I found him quite interesting, in the way all men who need two computer monitors for work find all men who need a pickup truck for work quite interesting. But we never became anything like friends.

The closest we got to bonding were the times when, in a spirit of anthropological curiosity, I asked him about small details of his life. The tattoo covering his left shoulder, for instance. It depicted a giant robotic claw reaching across his collarbone, slicing his flesh with metal talons, and ripping back his skin to reveal a bloody mess of muscle and machine parts.

“So, Matt,” I once asked, in my best NPR voice, “what made you decide to get that tattoo?”

He thought for a second, then shrugged contentedly.

“I dunno.”

I tried conjuring a follow-up and couldn’t. I’ve been told that one of my first words was ambivalent. To permanently brand oneself with any image, of any size, struck me as an inconceivably risky invitation to regret. And to pick an image that was huge, gruesome, and highly visible, for basically no reason? I was left gasping in confusion like a goldfish plucked from its bowl.

Which is all to say that when, five years after we met, Matt bought a beat-up used surfboard, I did not think, At last, a healthful pastime that might bring me closer to my future brother-in-law! I thought, Surfing is for lunatics.

Nothing in the years that followed changed my view. On one occasion, Matt arrived at a family gathering wild-eyed, his light-brown hair not so much tousled as beaten. He’d woken at dawn, he explained as though this were normal, and spent his morning being pummeled against rocks and slammed into the seabed. I would have found this alarming at any time of year, even summer, when the Jersey Shore is packed with beachgoers. But this was Christmas Day.

“Aren’t you worried about, you know, drowning?”

“Neh,” he replied, in his slightly pinched Jersey accent. I waited for him to elaborate. He didn’t.

“Okay. What about freezing to death?”

“The best waves are in winter,” he said, in what I could not help but notice was not an answer to my question. “You should try it.”

I declined his offer, not so much verbally as through my very existence. It was true that once, on a family trip to Mexico, I’d taken something described as a “surf lesson,” during which I knelt on a plank for an hour while a teenager rolled his eyes and pushed me toward a beach. But surfing—really surfing—was clearly different. Along with absurd levels of fitness and dexterity, it required a near-total lack of common sense.

It also seemed like a waste of time. My adult life had been defined by a line from Barack Obama’s first presidential campaign: “In the face of impossible odds, people who love this country can change it.” Even after leaving the White House, I’d remained a proudly earnest workaholic. I filled my days, along with most nights and weekends, with productivity. Writing books and TV pilots. Working on speeches for private clients. Volunteering for campaigns. While each project was different, when you zoomed out far enough the goal was always the same: to change the world.

Matt seemed to surf for no higher purpose whatsoever. He did it simply because he enjoyed it. That made no sense to me.

In 2018, Jacqui and I got married in Asbury Park, a Jersey Shore town best known as the spot where Bruce Springsteen got his start. The following year we bought a small vacation house there. It was listed, optimistically, as a “Victorian cottage,” and located a half mile from the beach. Sometimes while strolling the boardwalk, I’d see a gaggle of wetsuit-clad figures bobbing like apples in the sea. Every so often, one would turn, stand, and cruise toward shore.

It was noteworthy: these individuals were not my brother-in-law, yet they surfed. Still, nothing could change what was, in my opinion, the most relevant fact about Matt’s favorite hobby. If it was for people like him, it wasn’t for people like me.

Besides, I was an adult now, with a wife and a mortgage and two cats and intermittent back pain and a determination to make the most of my limited time on earth. To the extent I looked toward the ocean and thought, I wish I’d tried it, surfing was just another scribble on the map of roads not taken that people in their early thirties can’t help but draw. I should have seen Tom Petty in concert. I should have made out with Leah Franklin at that party freshman year. I should have learned to surf. Who cares?

The answer, as it turned out, was me. Enormously.

And all it took to realize it was the worst year of my life.

I’ll have another excerpt for you tomorrow, and I can’t wait for you to read it. In the meantime, It’s Only Drowning is now available wherever books are sold! And again, thank you for all your support during this crucial and crazy week.

Do you have an early review? A question about the writing process? A favorite (or least-favorite) sentence? Leave a comment and let me know!

Hmmm.

Comment: I’m looking forward to tomorrow’s chapter. And, mayhaps, my next check.

As much as it’s about what you wrote, it’s about how you wrote it.

Your book was just delivered here by Amazon. Both my husband and I will be reading it. Question is who gets it first?